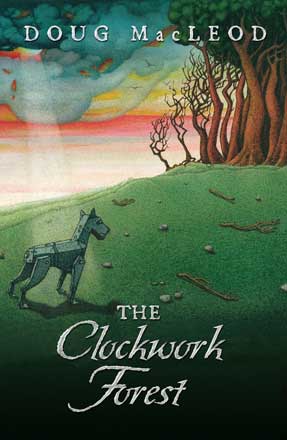

The Clockwork Forest

'Life would be a great deal easier if dead things had the decency to remain dead.’

Nothing is how it seems in the forest. Your best friend may turn out to be your worst enemy. A deadly poison can save your life. And two smiling children could become the most horrifying monsters of all.

Morton is sure of one thing, however. His four clockwork treasures are lost somewhere in this forest and he has to find them, or life is not worth living. Mind you, with bizarre perils lurking behind almost every tree, Morton’s life could end at any moment. If that isn’t bad enough, he is travelling without a handkerchief.

The Clockwork Forest started when Chris Drummond, a theatre director in Adelaide, asked me to write a play on the subject of abandonment. He wanted to call the play A Series of Tragic Abandonments, but I told him Lemony Snicket might get cross if we called it that, and the last thing you want to do is upset Lemony Snicket. Anyone who changes his first name to Lemony is clearly dangerous.

For inspiration, I read a story called Babes in the Wood, about these two babes who are abandoned in a forest. They die and get covered in leaves. Really, that’s about it. I decided to set my play in a forest, but I didn’t want the kids to die or get covered in leaves. (In my final version of the story, many characters meet ugly ends. One explodes, another is poisoned, yet another is already dead but still moving about – so there’s plenty of death for readers who like that sort of thing.)

Chris said he wanted the play to be scary but also funny. So I tried to work out if there are good things about abandonment. Buddhists believe abandonment is a good thing, because possessions make people unhappy, so you should abandon your possessions. I'm not a Buddhist, so I’m not giving you my car.

But reading a bit about Buddhism helped me to write this weird story about a lonely boy living at the edge of a dangerous forest, and the terrible but wonderful things that happen to him when he and his precious clockwork animals are blown into the forest by an immense storm. I thought it would be impossible to stage, but Chris Drummond managed it – as you can see from these pictures.

The production of The Clockwork Forest was eventually mounted by The Sydney Theatre Company. I was excited because I thought I’d be sitting next to Cate Blanchett on opening night. (She’s the artistic director of the STC.) But she was in London so I sat with Drahos Zak instead. He’s the artist who did the little pictures throughout the book.

I wrote the book after the play, and added some extra stuff. My grandma once told me about a luxury cruise she took with a lady friend. Through a series of strange events, they ended up having dinner at the captain’s table and their dresses started to melt. Before long these two grand ladies were sitting in their undies.

Grandma told me the story while I was driving her to my parents' farm in Ballarat. I had to pull over because I was laughing so hard. The story ended up in the book. If you want to know why my grandma’s dress melted, it’s in Chapter Eight. In Chapter Ten, we meet a bear who doesn’t appear in the play. He’s one of my favourite characters. As to whether he eats the girl or not – well, you’ll just have to read the book.

Chapter Ten

Hannah’s roll-top desk was the most handsome piece of furniture she owned. It had been fashioned from cherry wood by her father when Hannah was barely six years old and nursed a desire to become a great writer. There seemed so many advantages to such a vocation. Writers make their own hours. They are romantic. Their work is usually private. They can even write in their pyjamas if they choose, provided they are not working in a public library or restaurant. When she felt like writing, Hannah would change out of her normal clothes and into her pyjamas. She would sit at the beautiful desk, arrange the pieces of writing parchment her mother had given her for her birthday, fill the inkwell and dip in a pen. Then she would proceed to write absolutely nothing at all, sometimes for several hours at a stretch. While Hannah enjoyed the idea of being a great writer, she wasn’t keen on the actual writing part. In this, Hannah resembled almost every single writer in the world.

Somehow, the cherry wood roll-top desk had landed upright in the forest. It was completely unharmed, its landing cushioned by clumps of what Cuthbert would have called festuca, teosinte and whitlow but which normal people would have called grass. As Hannah approached the desk, wondering how she could possibly carry it back to her new house, she heard someone singing. It was a remarkably strong voice, which could hit very high notes and very low notes with ease. The two octaves at either end of a typical 88 key piano are quite useless. No one can sing them and they merely serve to make a stupidly large instrument even larger. And yet whoever was singing this song could hit the fourth A below middle C and the fourth B above middle C. At one point the singer trilled between both these notes. Hannah stopped, listened hard and tried to work out the source of the incredible bouncing voice. It was coming from behind a giant redwood. Hannah forgot about her desk for the moment and trod through the wet grass towards the tree. Sitting with his back hard against the tree was a huge male bear (scientifically referred to as a boar, but not in this story as it is confusing). His eyes were closed, his huge wet muzzle pointed up towards the forest canopy. The bear, oblivious to Hannah, breathed in a great mouthful of air then hit the fourth B above middle C. Hannah was so amazed by the singing bear that she did something very foolish. She made a gasping noise. The enormous brown bear immediately opened his eyes, stopped singing and bounded onto all fours. He snarled at Hannah and saliva dripped from yellow fangs. He made a hollow rumbling sound, then shook his head and roared. On massive clawed feet he stalked towards Hannah.

‘Don’t be silly,’ said Hannah. ‘You don’t mean to attack me. Any animal that can sing so well couldn’t possibly be cruel.’

Hannah wasn’t sure of the logic of this. Clearly the bear wasn’t either. He roared a second time and frightened every living creature for miles around, in particular the fifteen-year-old human that stood before him.

‘Don’t deny you were singing,’ Hannah said, standing her ground and wondering if this meant she was brave or merely stupid. ‘I saw you with my own ears and heard you with my own eyes.’

‘I think you have that the wrong way around,’ said the bear. Then he stopped in his tracks. ‘Oh dear, am I speaking?’

‘You are,’ said Hannah.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Very sure.’

‘I was hoping I could perhaps just growl and scare you away.’

‘Well, you’re no longer growling. You’re definitely speaking.’

‘Now, that is very unfortunate,’ said the bear, who seemed distressed.

‘But you have a perfectly wonderful voice,’ said Hannah. ‘It sounds deep and cultured.’

‘Yes,’ said the bear, a look of sadness spreading over his huge face. ‘All bears have wonderful voices.’

‘I didn’t know that,’ said Hannah.

‘No human does. We keep it to ourselves.’

‘Do you mean that I am the first human who has ever heard a bear speak?’

‘No, I don’t mean that at all. Many humans have heard us speak, but we try not to draw attention to it. We certainly don’t go up to humans, tap them on the shoulder and ask them the time.’

‘But if other humans have heard you speak, why is it still a secret?’

‘Once a human hears us speak, we have to eat them.’

‘That’s a shame.’

‘It is. You seem quite a pleasant human and I’m sorry you stumbled across me making up verses and singing them aloud. There are so few humans in this forest, I thought I would go unnoticed.’

‘I prefer not to be eaten,’ said Hannah. ‘I’m sure it would feel dreadful. For both of us, I mean.’

‘I can’t say for sure. I’ve never eaten a human being in my life.’

‘Why start now? I promise I won’t tell anyone your secret.’

‘I want to trust you, but I simply can’t. Humans are not like bears. You chatter all the time. You can’t help yourselves. One day you will be at a party and you will have drunk some elderberry wine. In the middle of a conversation about politics or umbrellas or something you will suddenly announce that you’ve heard a bear speak. And of course we know what will happen then.’

‘I’ll be sent to a head doctor.’

‘And when the head doctor finds there is nothing wrong with you, he will realise that you speak the truth. Then the humans will hunt the bears and imprison us. They will punch holes in our nostrils and insert rings attached to heavy chains. We won’t speak or sing. Not at first. So the humans will whip us until the pain is so great that we burst into song and people will pay to watch.’

‘I don’t think humans could be so cruel.’

‘Do I look like a good dancer to you?’ asked the bear.

Hannah wasn’t sure if the bear wanted her to flatter him. She sized him up: a massive creature who could kill in a hundred different ways but who looked as light-footed as a redwood tree.

‘No,’ said Hannah. ‘You do not look like a good dancer.’

‘Can you imagine me waltzing? Or doing the cancan?’

‘No, I can’t. Especially not the cancan.’

‘As it happens, I’m a terrible dancer. Bears are simply not made for dancing. We’re much better at sitting and sleeping and singing. But there are humans who catch bears and force us to dance. It’s agony. And there are other humans who pay to watch us.’

Hannah sighed. ‘I suppose you’re right to distrust humans.’

‘And that is why I must eat you,’ said the bear forlornly. ‘For the benefit of the entire bear population of the world. I’m awfully sorry about this.’

‘That’s all right.’ Hannah shrugged her shoulders. ‘Is there any point in my trying to run away?’

‘None. We bears may not be able to dance but we are experts when it comes to chasing things.’

‘What if I climb a tree?’

‘I’ll climb up after you, or push the tree over. It all depends on what sort of tree you choose to climb. Either way, you’ll end up eaten.’

‘So be it,’ said Hannah. ‘How should I prepare myself?’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Will you eat me with my clothes on?’

‘Of course. Otherwise it would be bad manners.’