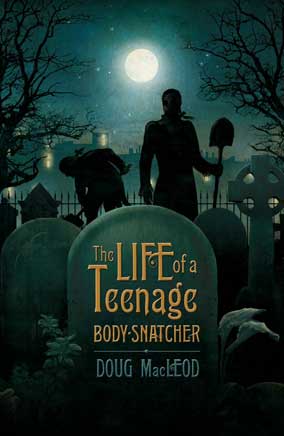

The Life of a Teenage Body-snatcher

‘You must think it’s strange that I’m digging up my grandfather.’

‘Not at all. I’m sure many young men dig up their grandfathers.’

Thomas Timewell is sixteen and a gentleman. When he meets a body-snatcher called Plenitude, his whole life changes. He is pursued by cut-throats, a tattooed gypsy with a meat-cleaver, and even the Grim Reaper. More disturbing still, Thomas has to spend an evening with the worst novelist in the world.

A black comedy set in England in 1828, The Life of a Teenage Body-snatcher shows what terrible events can occur when you try to do the right thing. ‘Never a good idea,' as Thomas’s mother would say.

The town of Wishall, where the story takes place, is entirely made up. But a lot of the other things are true.

I took my time over the six drafts, until my editor at Penguin, Dmetri Kakmi, was pretty happy with the end result. We realised this novel would be for older readers than my earlier novels, which is why the book is a Penguin and not a Puffin.

Even my final draft was changed considerably. Here is a typical page from the final draft, showing the changes that Dmetri and I made before sending it to the printer.

Some writers get a bit nervous with their editors, but I like it when Dmetri and I push the words around until we’re both satisfied that the book reads well.

Even after the first lot of typesetting (below), we continue to make changes, though not quite so many. We try very hard to leave the story alone after that.

My aim was to write a funny novel with some gruesome parts. I think that artist Pollina Outkina and designer Karen Trump capture that very well with the cover. Here are some of the earlier roughs they put together.

(

Designer Karen Trump searching for something gruesome to put on the cover of a book about body-snatching.

One of my favourite parts in the novel is where Thomas’s mad mother describes the facts of life to him

‘Thomas, you are sixteen,’ says Mother.

‘This is true.’

‘By the age of sixteen, most young men will have received certain instruction from their fathers.’

‘What manner of instruction, Mother?’

‘They will have been told the facts of life. Since you do not have a father, the task of telling you these facts must fall to another. I consulted my older brother, your Uncle Tarquin, but he said he would not do it. I thought he was being churlish until he informed me that he doesn’t actually know the facts of life. And so, it is with great regret that I must tell them to you myself.’

‘Not if it upsets you, Mother.’

‘You may recall, as a young child, you were attacked by a goose in a public garden. You cried.’

‘Nonsense.’

‘Do not be ashamed. You were three and the goose was large. You were wading happily in a shallow ornamental lake at the time. There were some geese, quite pretty creatures. What you didn’t realise was that two of the geese were in the act of procreation. Geese mate on the water, you see, but as a three-year-old you were not to know that. Their honking amused you so you ventured close to them. Furious at being interrupted, one of the geese (I imagine it was the male but I am no naturalist) swam after you and pecked at you fiercely, its massive wings flapping and causing the water to spray up. I called for help but when none came I sat and watched peacefully. After half an hour or so of being pecked by the goose, you emerged, crying, from the lake. I dearly wanted to hold you in my arms but there was algae on you, so I patted you once firmly yet maternally on the head. You asked me why the goose had assaulted you. I replied it was because the geese were busy making baby geese and did not appreciate your intrusion. An inquisitive child, you asked how the baby geese were actually made, and I said that the mother and father geese do a brief water ballet then nine years later the baby geese emerge fully-formed from the mouth of the female when she yawns. Do you recall that?’

‘Everything except for the crying.’

‘I lied, as I’m sure you realise. Baby geese – goslings – come from eggs that emerge from the female. This happens after the male has impregnated the female via that part of the goose where a cook might insert an orange. It is exactly the same with humans and nothing to be ashamed of. I hope this talk has been of some benefit.’

‘Thank you, Mother.’

As the story continues, the mother becomes madder and madder. She was great fun to write.

‘You were out last night,’ Mother says, with no great interest.

‘I’m afraid I had to go to London again. It’s most dreadful about the fire.’

‘There’s been another fire in London?’

‘No, here. In Wishall. There was a fire last night.’

‘Well, I’ve heard nothing about it so it can’t be very large.’

‘It’s actually still blazing, Mother, and has wiped out nearly a quarter of the town.’

‘Why on earth didn’t you tell me earlier?’

‘Well, I thought you’d know.’

‘Your father would have told me. Sitting over muffins and jam he would have told me in lurid detail about the destroyed buildings and loss of life.’

‘I don’t think anyone’s actually died.’

Mother looks disappointed.

‘But we cannot be sure,’ I say.

Mother cheers up immensely. ‘I do miss those conversations with your father.’

‘Is there nothing else you miss about him?’

‘Yes. There is nothing else.’

‘I am sorry it wasn’t a happy marriage.’

‘It was moderately happy for a year. Then it turned very bad indeed.’

‘When I was born.’

‘Yes, but please don’t blame yourself.’

‘Did father not like me?’

‘I thought at first that he did. He would bounce you on his knee and tell you sonnets from Shakespeare. Actually, I was rather angry about the sonnets. I don’t think you should read love poems to a baby because you might give it ideas. A lecherous baby is most undesirable.’

‘I don’t remember the sonnets.’

‘Oh, and I recall something else. He made you fly.’

‘How on earth did he do that?’

‘Well, it wasn’t actual levitation. Your father would hold you high over his head and run with you through the house. You loved it. But your father stopped doing it when you were sick on his hair.’

‘Then father did like me?’

‘He didn’t enjoy being vomited on, but yes, he was quite well disposed toward you.’

‘What happened to turn the marriage bad?’

‘Haven’t we had this conversation before?’

‘Bits of it. You always try to change the subject.’

‘Mrs Greenough informed me that they have just found a feral child in Germany. It raised itself in a forest, apparently. It is quite wild and completely lacking social skills. I’m frankly amazed that the Germans could tell the difference.’

‘You are doing it now. Please don’t alter the subject. What turned the marriage bad?’

‘We grew apart. Then your father was trampled to death by a horse. I cried, of course. They had to destroy the poor creature.’

Although the town of Wishall is made up, other locations in the story do exist. Camden Lock is where we meet an insane publisher called Rupert Higgins. There are quite a few insane people in the book, but what do you expect from a romantic adventure that involves body-snatching? A gypsy once stopped me at Camden Lock and told my fortune. (This gave me the idea for the gypsy in the book.) She sold me a sprig of heather, which she said would bring good luck. Ten minutes later I fell down some stairs. I went to get my money back but she’d gone.